The Creative Process in Landscape Photography

For over forty years I have been a photographer. Using film, I quickly learned that slowing down in my own artistic process revealed photography as a contemplative and creative act every time shutter clicked. The cameras I used then were just as heavy as the DSLR’s of today. We did not have the mirrorless cameras, lightweight carbon fiber tripods and other accessories that we can order online with next day delivery. A trip into the field, felt like I needed a pack mule to carry my gear.

Back then, I calculated my exposure by looking at how the light and the shadows fell upon and interacted with the subject, then I processed my own film into negatives and prints in a wet darkroom. To aid in the process, I saved up some money as a high school student to afford my first selenium light meter. I went to the local camera store – yes, an actual place – and ordered it. About ten days later, I picked it up – that was “quick ship” then. Film was expensive – so every shot had to count. It was a slow process at best and one that required attention to detail, a command of the technical aspects of photography and patience. When I started in editorial work, I had to be able to the do same much faster for sports and breaking news. Today, the digital world allows us to shoot hundreds of images and simply delete the ones that do not make the cut – the change in skillset between photographers then and now, I believe, takes it roots, from this concept and the advanced equipment we all use today. However, hand me a camera with no automatic functions, no light meter and a roll of film – I will be able to shoot, process and print without difficulty.

Photography has provided me a window on the world – yes, that sounds a bit clichéd, but it is an accurate statement. Every day, I get to see the world in a new way, tell a new story and experience something new or something routine in a new way.

Today, in the digital era, there is a mindset among many photographers just to get an image, sometimes any image – not “the image” – that represents the subject at hand. It is paramount to understand that the camera is a powerful tool – a powerful creative tool, which we have opted to pick up and use. Artistically, we each have our own path, our own signature and our own style. But it is deeper than that, so much deeper. Our craft, in this case photography, demands more from us.

It demands, what I can only equate to the Japanese word “Takumi”. As a direct translation: Master Craftsman. I can simply say the word and use it or extend it to a philosophy, where it dons a greater sense of being - putting all of your creative energy into what you create, so that energy is transferred to anyone who experiences it. This energy is born from how we choose to see the world through our viewfinder; how we see things we’ve never seen before; how we share our unique experiences and way of seeing the world. Ideas and vision are ideated and created by external forces.

Knowing this, there is an internal struggle within my field process not allowing the viewfinder to burden me with tunnel vison. Essentially narrowed by the restrictive frame, photographers may miss important things in the landscape around them. In my editorial work the camera evolves into a shield for photographers to sometimes hide behind – it protects them from interacting with the people or fully engaging with the environment.

Digital and film, photography still require looking, seeing, thinking, interpreting and expressing. I stop at a scene and see an image in my mind - I make the photograph. Then I present it to the viewer as a representation of what I saw and felt at the time the shutter is tripped. For that elemental reason, we, as photographers, must become more in tune with our surroundings, our emotions and the intentions of our work.

Creativity is about coming up with something new and unique – it is about doing things differently. When doing this for ourselves, having a bad day photographically in an idyllic landscape is not a big deal. Doing this for a client, who has commissioned a piece, means having the ability to operate on a much higher level consistently and have far fewer “bad days”. But being different just for the sake of being different is never enough. Vision and purpose must exist within us and our work to create something meaningful, beautiful or otherwise significant. This is the challenge every time I pick up the camera.

In landscape work I have now created my own ritual as a method of approach to a landscape session. Borne from the premise that photography is visual communication - it is the obligation of the photographer slow down the process of capture, heighten and intensify one’s own awareness of the surroundings, thus bringing greater intention to the resulting work.

This is a process that leaves the camera in the bag for at least 10 minutes after arriving at a new location, allowing time for smells to be experienced, wind to be felt and the sunshine to fall all around me. It is time spent to become “in touch” with what compels you and why. It is a time to experience the moment and the scene to be communicated back to the viewer. Photography is a singular experience isolated to the photographer and the subject and then the viewer with the image.

This short pre-session ritual has a place in my commercial work as well – just sitting and talking with a subject, learning about their personality and connecting with them has provided at least one great shot instead of ten okay shots. But more than that – friendships have developed, language barriers have been crossed and stories have been told that transcend cultural differences simply by harnessing the power of photography.

My process also dictates the use of forced limitations as the genesis of creativity. This originally made me feel constrained and confined, but embracing the limitation has produced a wellspring of opportunity.

In this series of photographs, I chose to carry just one camera and one lens – this lightens to load as far as equipment, but also restricts my vision into just the angle of view provided by both camera and lens. My choice for the image series is the Leica M Monochrom (Type 246) with a Voightländer 75mm f1.5 lens. This camera lacks a color array – thus captures only monochrome images, further restricting the latitudes of the photograph.

In June of this year, I visited McConnell’s Mill State Park in Western Pennsylvania. There is a covered bridge, a waterwheel and a rapidly flowing river strewn with large boulders in the park. Walking along the river I stopped, set down my camera equipment and took out my reporter’s notebook. Closing my eyes and removing vision from the available senses, I could hear the rapids more sharply, there is an “earthy” smell to the primeval forest here and a smell to the water wafted on the gossamer breezes swirling above the flowing river. Scribbling down a few notes in the humid afternoon heat, I saw many other people sitting on rocks, enjoying picnics in the shade and finding solace in the sounds of the water. I chatted with one person walking past me – they stopped - having recognized my Leica, but having never actually seen one. Come to find out – McConnell’s Mill State Park is a weekly trip for them.

It took longer than ten minutes – more like forty-five, but I had the theme to my photograph jotted down in my notebook. Steadfast and unchanging (rocks) but providing solace and calm (water). The restrictive pallet of monochrome permits the photographer the freedom to strip away the distraction of color and expose both the textures and compositions lying latent within the frame.

I set up my tripod and camera deciding on a composition.

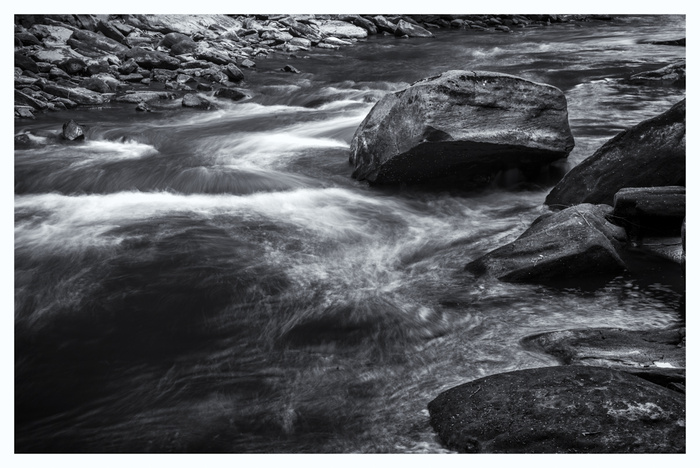

This image represents exactly what I saw at the river’s edge that June day. There was a 3-stop difference in light from one side of the river to the other and the water was moving reasonably swift. The large boulder – most likely existing in that spot before I was born and continuing to occupy it after I depart this world – anchors the photograph. Using a rule of thirds composition style, it occupies the point of intersection for the horizontal and vertical lines within the frame. In a photographer’s vernacular, these are “anchor points”. My mother – a painter – terms them as the eyes of the painting. How ever they are termed, the concept remains the same.

The first correction I made was using a three-stop Singh-Ray Galen Rowell Graduated Neutral Density (ND) Filter to balance both the foreground and background. I have an affinity for the square P-Mount Filters, which can be rotated to an angle matching the line of lighting change. The three-stop filter did not eliminate all of the hot spots, but it did get the vast majority toned down to where they could be worked with in post processing. So far, the composition and exposure are near my vision, but there is still more work to do.

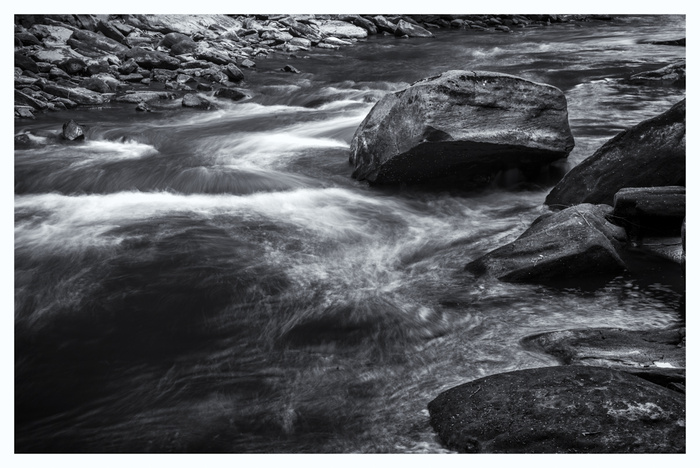

In the above image, a 3 stop Singh-Ray George Lepp Solid Neutral Density (ND) Filter was added along with the three stop Singh-Ray Galen Rowell Graduated Neutral Density (ND) Filter. This balances the foreground and background, while providing neutral density to slow the shutter speed softening the rapids. This was a step in the right direction, but not quite what I had in mind.

In the above image, a two stop and a three stop George Lepp Solid Neutral Density (ND) Filter are combined with three stop Singh-Ray Galen Rowell Graduated Neutral Density (ND) Filter. This balances the foreground and background and provides five stops of neutral density to slow the shutter speed softening the rapids. Excluding the conversations with passersby, I had spent an hour at the location making photographs and waiting for clouds to pass brightening the opposite side of the river back to the original three-stop difference.

In post processing I tend not to crop Leica captured images, only dodging, burning and contrasting as I would in the traditional wet darkroom. In my film days, I enjoyed having a black “stroke” border on my prints to show the viewer that it was “uncropped” at the time of print. In the “film days” I was using a Beseler 23CII enlarger with two negative carriers. One of these I carefully marked and then filed to create a larger print area than the image portion of the lucite strip. I was able to use this carrier with my negatives in the printing process – it was not perfect, but that was part of the appeal in my early work. I now apply this in Lightroom, although it does affect the image format slightly.

In order to improve our vision, we must embrace limitation as an instigator of creativity. The photographers must allow themselves to take risks and embrace the freedom to fail. Trying to be creative, means attempting shots that you haven’t done before.

Remain steadfast to your vision and the visual communication within the frame. Never force yourself to capture an image based on uniqueness alone – allow the metamorphosis of an image to happen naturally, so that it aligns with your own vision and the visual language you are speaking.